The skyline-silhouette: a recurring design where the most beautiful and recognisable of a city’s buildings are amalgamated into a continuous block, often used for garish pixelated canvases. Durham’s version with its Norman architecture of spires and crenellations designed to impose a religion and repel the Scots, omits our contentious but well loved brutalist architecture. These buildings are a unique connection to a generation defining engineer who worked on the Sydney Opera House before founding a world-leading architecture company. His buildings and accompanying philosophy continue to have a resounding global impact, yet ultimately never make it onto the walls of coffee shops where alternative milks are an extra 50p.

One of the most influential engineers of the 20th century, Ove Arup was born in Jesmond, Newcastle, in 1895 to Danish and Norwegian parents. A master of pre-cast concrete structures, some of his earliest and arguably finest work is a trio of structures in Durham. However, despite his global acclaim, these buildings have faced neglect, mismanagement and in some cases, the threat—or reality—of demolition. What is it about these buildings that keeps them so perilously under-threat, disavowed from our acclaimed skyline?

Total Design

Ove Arup is often described as “the philosopher engineer". Total Design is his concept that brings together all elements in the creation of a structure, striving for excellence and due care down to the smallest details. For Ove, this extended beyond the physical structures and where it was sited, to the people involved in building them and those who would occupy them. His designs, his company and the way he lived were part of this all encompassing philosophy.

The Sydney Opera House was where he first cemented himself as someone who would steer the course of modern architecture long into the future. Constructed with massive pre-cast concrete beams, the building was the very first to incorporate computer-generated calculations into its design and as such was a marvel in its complexity. From this project grew Ove’s reputation, as well as his company which would go on to span the world, eventually amalgamating into The Arup Group. Now with 94 offices in 34 countries 17,000 people are employed true to Ove’s ethos, with the company structured as a trust, employees past and present are given a share of the operating profit.

“We are an organisation which is humane and friendly despite being large and efficient. Where every member is treated not only as a link in a chain of command, or as a wheel in a bureaucratic machine, but as a human being whose happiness is the concern of all.”

-Ove Arup

The first bridge project by what would soon become the Arup Group, Kingsgate Bridge was the only project that Ove personally oversaw both in design and construction. Commissioned by Durham University, it was built in two concrete halves either side of the river, poetically swung into place and linked by an expansion joint that forms an intersecting T and U, for Town and University. Perhaps Ove felt as I do, that this project embodied the aspirations of his Total Design ethos. His ashes were spread at the bridge on his death in 1988 and in 1998 it was awarded Grade I listing status, the same as the cathedral.

Adjacent to the bridge stands Dunelm House. Another building designed under his guidance, narrowly escaping demolition in 2016 when Durham University announced plans to tear it down, citing repair costs of £14.7 million. After two appeals, however, the building was granted Grade II listing.

The thousand-year-old Durham Cathedral stands in gentle contrast to Arup’s modern structures, like an eclectic congress of garden ornaments outside a bungalow—a unicorn beside a ferret, a greyhound alongside a gnome. Yet, while these buildings seem to coexist with an unusual harmony, Arup’s work has often attracted criticism. Some are intolerant of his modernism and in favour of the medieval grandeur which is so ubiquitous in Durham. Compared to their aesthetics, the purposes of the buildings are so rarely contrasted: the cathedral, a monument of Norman power designed to oppress and make servants of people versus Arup’s works, aimed to welcome and serve the people. That’s not to say I find the cathedral oppressive, I like it, but I’m sure after the Harrying of the North by the William the Conqueror in 1069, an over 100,000 person genocide that quashed northern rebellion, the sight of the cathedral for those with living memory of the atrocities would have been oppressive.

... so great a famine prevailed that men, compelled by hunger, devoured human flesh, that of horses, dogs, and cats, and whatever custom abhors; others sold themselves to perpetual slavery, so that they might in any way preserve their wretched existence.

The Kingdom Of Northumbria

One of my favourite things about Dunelm House is the many ways in which you can interact with it. You can explore the building without passing any gates, from multiple directions. It provides useful shortcuts for the commuting pedestrian, as well as a non-oppositional interior reception to those maybe needing to pop in and use the toilet. Arup’s philosophy of design and post-war optimism is so evident that in my over-optimistic mind these structures contain the promise of a different future for the North. When I see them so deliberately neglected into disrepair it fills me with a sense of dread and longing. Disregard for these buildings is the familiar and intentional decimation of our culture.

Peterlee, the first UK town built by public petition, was filled with similar architecture. Many people relocated there from "Category D" mining villages, which had been deemed unfit for habitation and were resultingly cut off from support, encouraged to slowly die. Yet while the modern brutalist structures that would rescue us from villages with ‘No economic future’ were built, the accompanying philosophy of optimism and progress was often lost. This decay of purpose—whether from economic policies or cultural attitudes—raises the question of what the North might have become had these ideals been fully realised. What if Northern people had spent less time on scratch cards and more time on brass rubbings? Maybe now there would be a wall guarding the Humber, the great Northumbrian Kingdom of old restored, thriving along with an independent Scotland and North Wales?

Shoot to kill orders along the wall for anyone from below Sheffield, tax loopholes and cross border tobacco smuggling encouraging destabilisation of the nearby economy in Nottingham. As entertaining as these fantasies may be even AI struggles to pervert Ove’s ethos and create things to divide or intimidate. His work aimed to integrate buildings into cities, welcoming individuals and enriching communities. They fulfilled their purpose and more, embodying the optimism and ambition of a brighter future. For someone who sought to bring together the architects, engineers and builders, it’s fantastic to imagine a city under Total Design instead of just a handful of buildings. That’s just what his architecture does, it inspires you to interact with it, to graffiti on it, to climb it (and to image famished hordes of southern people being repelled by it).

The Mast

My personal fascination with these buildings, which I think would have amused Ove, is in climbing them. Starting when I found myself huddled in a bush at 2am outside Durham Constabulary Police Headquarters building, wearing a climbing harness. I awaited a lapse in movements that never quite came, in order to begin an exciting 49.5m climb up a dormant telecommunications mast. While I never got the chance to even touch the tower, such was its guarded proximity to the headquarters, I recently sought it out and was able to make contact with it for an interview.

As part of Durham Constabulary’s move to Aykley Heads just outside the city centre, the mast was Built in 1968. It was designed to ensure narrow margins of wind sway for the radio communications and to avoid guide ropes or unnecessary width that would disturb views of the cathedral (so it can continue to oppress everyone).

In 2012, the police were granted planning permission to demolish and relocate the headquarters elsewhere on the Aykley heads site, with reported cost savings of £750,000 per year and an estimated £20 million from the sale of the remaining land. Permission was granted alongside this to dismantle and relocate the mast, as selling the land with the mast would have apparently taken 1£ million off the price.

With delays due to a colony of endangered great crested newts in the vicinity of the site, the new £14 million headquarters was opened in 2015. In what is a hilarious metaphorical anecdote, the time capsule that was buried during the building of the 1960’s headquarters, was unable to be located before the move. The capsule is now probably underneath a garden hot tub in one of the ‘48 executive homes’ that were built on the site. It’s possible too that the police found it and simply threw it into a nearby pond when they discovered it contained instructions for the safe deconstruction of the mast. In 2022, the police applied for permission to demolish the mast, citing damage during its dismantling, rising storage and maintenance costs, as well as an apparent hatred of the structure.

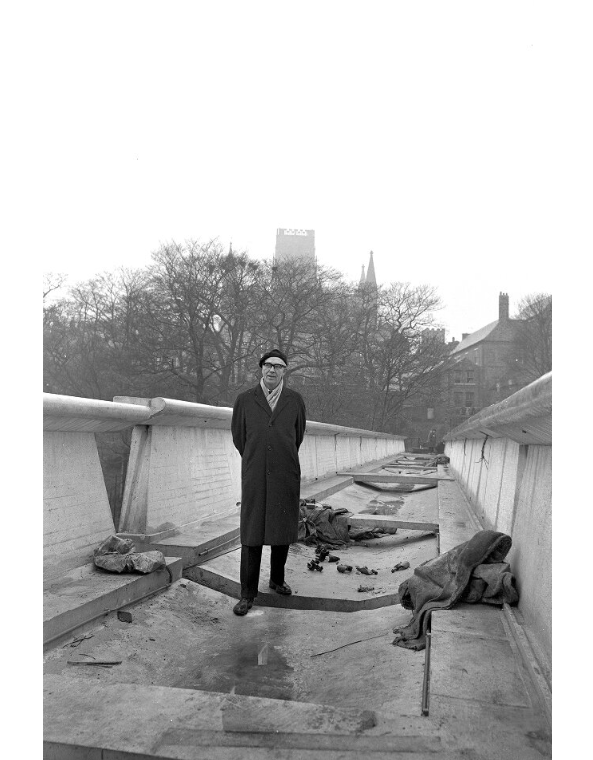

Seven years later, the mast still languishes in a cage with the façade of a “temporary solution”. A ragged tarpaulin flaps, barely concealing any of the structure. It lies in stark contrast with the £14 million headquarters building, designed by Ryder Architecture. Gordon Ryder and Peter Yates who started the firm, first met in Berthold Lubetkin’s office, the original architect behind Peterlee and a collaborator of Ove Arup.

The metal designed to capture lightening and disperse it to the ground does not reach the sky, the ladder rungs are horizontal. The structure is stored so unlovingly, without care, in a way that attempts to provoke us into hating the mast, to see it as pathetic and worthless. There is beauty in these mistreated structures, like when pieces of a building wash up on the shore in Hartlepool, eroded by waves, their original purpose disguised: a brick with edges rounded by the sea.

‘Comparing the mast to Durham Cathedral is nonsense.’

‘I think people would rather have police officers and PCSOs than a redundant mass of damaged concrete.‘

-Comments from a 2023 press release by Durham Police and Crime Commissioner Joy Allen

While Joy Allen is right to ask for permission to destroy it, it’s the rhetoric from someone who serves our communities that I find distasteful. I understand that these choices are forced upon us, by our predecessors and by current financial constraints. These comments are made whilst being complicit in actively damaging the concrete and encouraging its redundancy. To then ascribe a binary choice to a situation of their own making, makes my head sting. It’s reminiscent of the enforced ‘choices’ the North has always been faced with, stemming from policy, not scarcity. It’s the purposeful erosion of our culture, this time brazen, laid out in a field for all to see.

Despite the sadness of seeing this great structure laid low and ailing, it is still beautiful and imposing. I am somehow grateful for being able to see it in this context: a sleeping giant. Now feels like the right time to visit it, to hop the fence, examine this incredible structure up close. Given the importance of Ove, to the North and the world, this mast must be re-erected.

You can visit the tower and leave a review here: https://maps.app.goo.gl/FVdMWSwZSWqJ1TnKA

Or help get it to number 1 on Tripadvisor by leaving a review here:

https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Attraction_Review-g190832-d28395941-Reviews-Durham_Police_Mast_County_Police_Communications_Tower-Durham_County_Durham_Engla.html

You can see the second article in this series here:

Spot on. A lot of that chimes with me. I'm all for preserving our heritage, but if all we do is preserve, what will represent our era to future generations? At this rate, we'll turn our towns in Beamish and complain that there's no life in them any more.